Pakistan’s government is charging ahead with plans to auction 5G spectrum in the first quarter of 2026. The initiative is being framed as a major leap in digital transformation, one that policymakers believe can accelerate economic revival and strengthen Pakistan’s global competitiveness.

Officials argue that the promise is substantial. They point to lightning-fast speeds, ultra-low latency enabling smart cities, an Internet of Things boom across agriculture and manufacturing, and projections of billions of dollars added to GDP. The plan involves releasing 606 MHz of new spectrum across the 700, 1800, 2100, 2300, 2600, and 3500 MHz bands, more than doubling current capacity to reduce congestion and unlock technologies such as eSIMs, NFC payments, and wireless charging.

Supporters cite international projections to justify the urgency. GSMA reports suggest mid-band 5G could contribute more than $30 billion to South Asia’s GDP by 2030, with Pakistan potentially capturing a meaningful share.

Ericsson’s analysis of emerging markets estimates a $4.7 billion uplift for economies like Pakistan, driven by smart rural clusters, Industry 4.0 adoption, remote healthcare, precision agriculture, tele-education, and efficient logistics, provided infrastructure keeps pace.

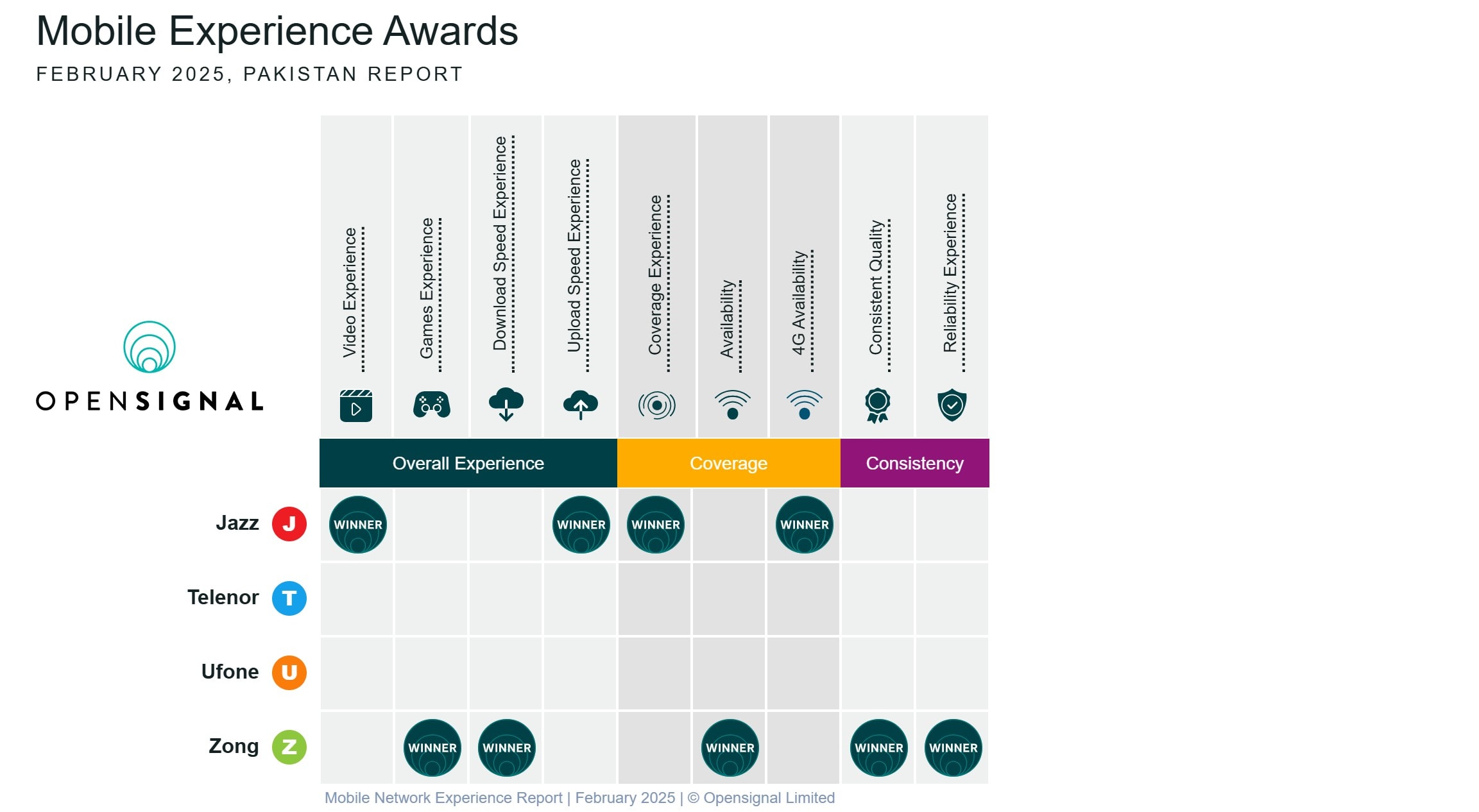

However, beneath the optimistic projections, fundamental readiness concerns persist. Pakistan’s current spectrum allocation stands at just 274 MHz, among the lowest in the region and roughly half that of peers such as Bangladesh or Thailand. Users routinely complain of call drops, buffering, and average 4G speeds of only 17 to 20 Mbps. According to OpenSignal’s Februrary report, here is the current situation of mobile networks across Pakistan:

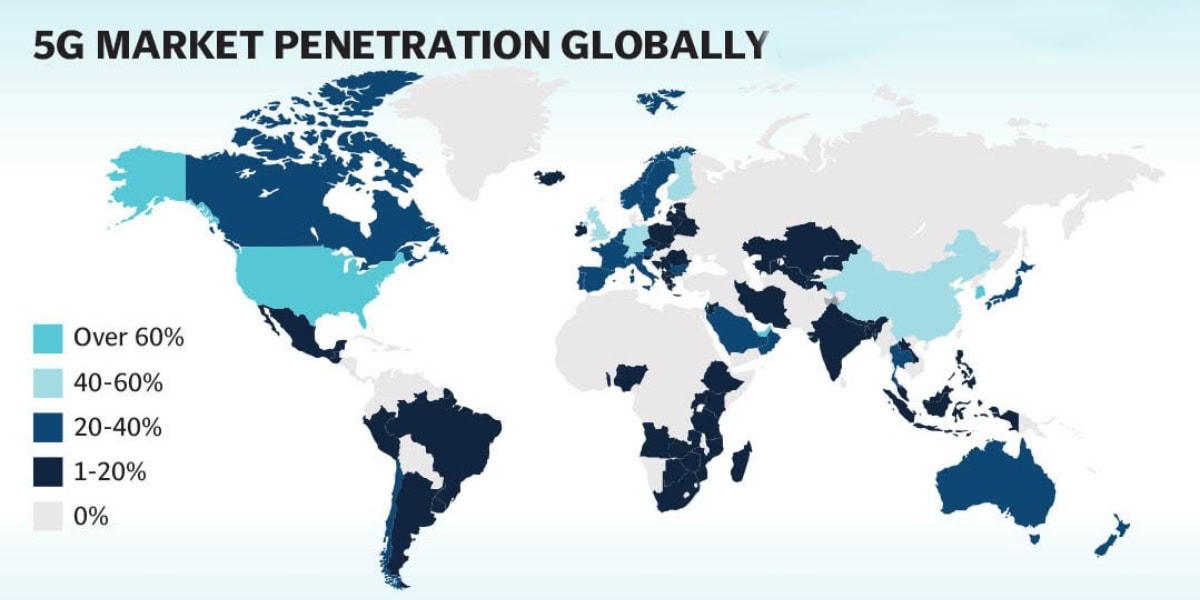

Mobile broadband penetration remains between 57 and 60%, with 148 million 3G and 4G users out of roughly 196 million subscribers. More than 40% still rely on feature phones, while around 10% lack any mobile device. Smartphone adoption is constrained by cost, with 5G-compatible handsets accounting for less than 5% of the market due to entry prices of PKR 40,000 to 50,000 and taxes and duties that can reach 40%.

With fewer than 2% of mobile users carrying 5G-enabled handsets and just 15% of telecom towers connected to fiber, the question of Pakistan’s readiness for 5G remains a million-dollar one.

The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority has echoed similar concerns. In its annual report, the PTA stated that “the deployment of 5G requires a substantial investment in terms of upgrading existing networks and expanding infrastructure with the installation of small cells, advanced antennas, and extensive fiber optic backhaul.”

The regulator warned that this “imposes a considerable financial burden on telecom operators as securing the required capital can become a challenge for them, particularly in a competitive market with price-sensitive consumers.”

The PTA further noted that “the return on investment may take time, making them cautious about committing large capital expenditures upfront,” adding that “government incentives and Private-Public Partnerships (PPPs) may hence be crucial to ease this financial strain and promote necessary investments.”

Operators themselves remain far from enthusiastic. They continue to demand rupee-based pricing instead of dollar-pegged spectrum fees, long-term interest-free installment plans, multi-year moratoriums, and duty waivers on imported equipment. Their concerns stem from harsh economic realities, including some of the world’s highest sectoral taxes, inflationary pressures, energy costs, and one of the lowest average revenues per user globally.

Industry experts also warn that delays have already cost Pakistan between $1.8 and $4.3 billion in forgone benefits. Prolonged litigation over 140 MHz in the 2600 MHz band and merger delays, including the PTCL-Telenor merger that took more than two years to clear, have further compounded uncertainty.

Initial rollout plans expose sharp inequalities. Early deployment is expected to focus on major cities such as Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Multan, Peshawar, and Quetta, while rural Pakistan, home to nearly 70% of the population, continues to struggle with inconsistent 4G coverage. High-band 5G requires dense tower networks, while mid- and low-band deployments needed for broader reach demand billions in additional investment.

The PTA has warned that “bridging the digital divide constitutes a significant challenge in the rollout of 5G in Pakistan,” noting that while urban areas may benefit quickly, “rural and remote regions risk being left behind due to the high costs and logistic hurdles of extending 5G to sparsely populated areas.” The authority also flagged handset availability, stating that “the availability of 5G handsets is also a barrier to widespread 5G adoption,” and emphasized that “ensuring equitable, nationwide access to 5G services is crucial for inclusive economic growth and social development.”

Public awareness remains another hurdle. According to regulators, “promoting public awareness and 5G adoption is another challenge as many consumers and businesses are yet to fully understand the benefits and potential of 5G.” Concerns around health effects and misconceptions could further slow uptake, prompting calls for “public education campaigns” and “transparent communication” to build trust.

From the operator side, Aamir Ibrahim, CEO of Jazz, has articulated a pragmatic stance.

“For retail consumers, the priority is simple — faster, reliable, and affordable internet across Pakistan. Whether it is 4G, or 5G matters less than the quality of experience.” He added that, “with adequate spectrum, existing networks can already deliver significantly higher speeds nationwide, strengthening broadband performance today.”

While Jazz has a structured roadmap for next-generation technologies, Ibrahim stressed that “5G’s impact will be maximized when the right conditions are in place — sufficient spectrum availability with viable conditions, device readiness, and a supportive digital ecosystem.”

He noted that “preparing these foundations ensures that the transition to 5G delivers real economic and social value from the outset.” Emphasizing long-term thinking, he said, “policy decisions around spectrum and next-generation networks should be guided by long-term economic outcomes — productivity, innovation, and digital growth across industries.” He concluded by stating, “This is not a government-versus-operator debate and not even a technology generation debate; it is a shared responsibility to ensure connectivity delivers meaningful benefits for both the citizens and enterprises across all economic sectors of Pakistan.”

Not all experts believe full readiness is a prerequisite. Parvez Iftikhar, founding CEO of the Universal Service Fund and an ICT policy consultant, argues that “no country has to be ‘completely ready’ with respect to infrastructure etc. for 5G before launching 5G.”

According to him:

“The technology will proliferate at its own pace, and it will get deployed wherever it finds its usefulness and wherever it finds conducive conditions.” He added that “that’s why the government should enable the industry but leave the timing of deployment to the industry players.”

On paper, 5G’s benefits are compelling. In practice, without affordable devices, robust nationwide 4G, deep fiber penetration, and meaningful rural inclusion, those gains risk remaining confined to a privileged few. Pakistan’s digital ambition is undeniable, but the unresolved question remains whether 5G represents an urgent necessity or a costly indulgence. Leapfrogging may look impressive in policy documents, yet bypassing foundational infrastructure risks widening long-term connectivity gaps rather than closing them.

6 min read

6 min read